Your organization has one job: Deliver value to your customers. But not all kinds of value are the same, and not all manners of working to deliver value are equivalent. Do you know where your organization is devoting its resources? Let’s examine these parameters and how you can improve the way you work to deliver both kinds of value.

Value and Work

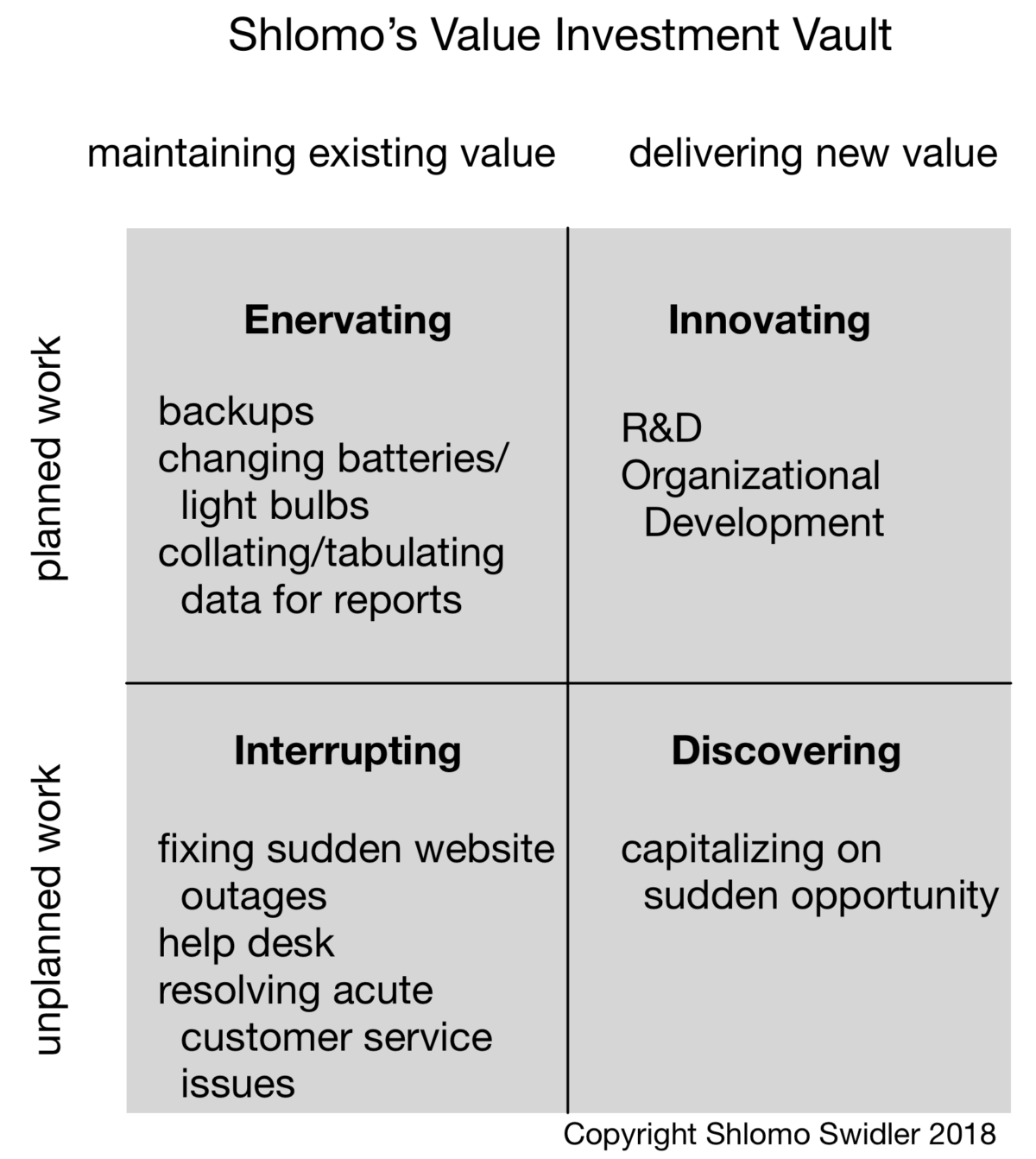

There are two types of value you can deliver: You can maintain old (already-delivered) value, for example you can restore your website when it goes down or you can repair a failed product. Or, you can develop new value, for example performing R&D for new or improved products. Both types of value are important to customers.

Likewise, there are two ways you can work to deliver value: in a planned fashion—following a product roadmap or pre-scheduled plan, or you can perform unplanned work, addressing acute issues as they arise—for example changing dead batteries or replacing depleted printer toner cartridges. Both manners of working are necessary and important.

Value vs. Work

Let’s take a look at the diagram showing Shlomo’s Value Investment Vault for some interesting insights. In the top left quadrant you have planned work that maintains existing value. We all know that light bulbs and printer ink will eventually need replacement, and we could (given the discipline and metrics) plan to replace them on a schedule. This kind of work is repetitive and enervating, devoid of creativity, but performing it in a planned fashion is preventive and avoids frustrating interruptions. Such work is ripe for automation and robotics.

In the lower left quadrant lies unplanned work that maintains existing value. Most often we don’t know when the website will suddenly go down or the truck will get a flat tire, yet we must repair them in order to restore service. This kind of work is characterized by interruption, frustration, and urgency. While there is no way to eliminate this type of work, you can reserve enough extra capacity in your organization so it does not unduly impact planned work.

The upper right quadrant is where innovation happens. Your products and your teams improve in measured, planned steps. But don’t forget about serendipity: The lower right quadrant is where you can capitalize on discovering new value from previously unknown or unpredictable situations.

How is this Useful?

Use the Value Investment Vault as a diagnostic tool to analyze your current activities. How much of the work your organization performs falls in each of the above quadrants? Poor performers find themselves on the left side of the diagram most often, and seldom have the capacity to innovate, let alone exploit and discover new opportunities. Elite performers spend most of their time on the right hand side—and most of that in the upper right quadrant delivering innovation—and they reserve enough capacity to easily handle unplanned work.

If you need help getting there, you know whom to call.